- 1865

- 1904

- 1905

- 1916

- 1919

- 1921

- 2010

- 2016

Should the US use eminent domain to preserve more land?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (Yosemite Valley, national parks, and the environmental movement) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will also develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try initiating a seemingly impromptu conversation by asking the class: “What does everyone think of our city’s public parks… are they great fun, just okay, or not much fun?” You could provide more information about the public parks. Students may or may not particularly care for the park or its playground equipment; however, the very fact the park and its equipment exist is the important concern for this conversation. While students share their thoughts aloud, you can negotiate responses by categorizing them into broader themes such inclusive access and benefits for all in the community, how the city became the owner of that particular land, how limits on the commercial use of that space were decided, etc. Together, the class may want to create a list of benefits of public parks and contrast those benefits with the potential other uses (commercial, private) of that space. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As responses wane, you can share that today students are going to extend the conversation to ask, not more about the local public parks, but about the national and international equivalents. “Should the United States use eminent domain to preserve more land and accomplish conservation goals?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open-ended questions around which this problem-based historical inquiry (PBHI) activity is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is the environment, and citizens of many nations throughout the world have had to think through their answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.Problem-based historical inquiry* (PBHI) is an approach to teaching students about the past. One of the tenets of PBHI is that learning should be purposeful: lessons should be centered around open-ended, societal concerns that call for students to engage in real-world problem-solving, make decisions, and act. Lessons should afford students sufficient time for sustained focus on content and skills and to think deeply and seriously about facts, definitions, and values. Instead of memorizing information from a textbook or lecture, students have a more authentic purpose with PBHI: deep, sustained learning and struggling with problems of the past to more meaningfully address problems of their present and future.Which of the two compelling questions presented in this lesson would you center instruction around? Why?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013). Designing web-based educative curriculum materials for the social studies. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2).You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own best interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).

PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”

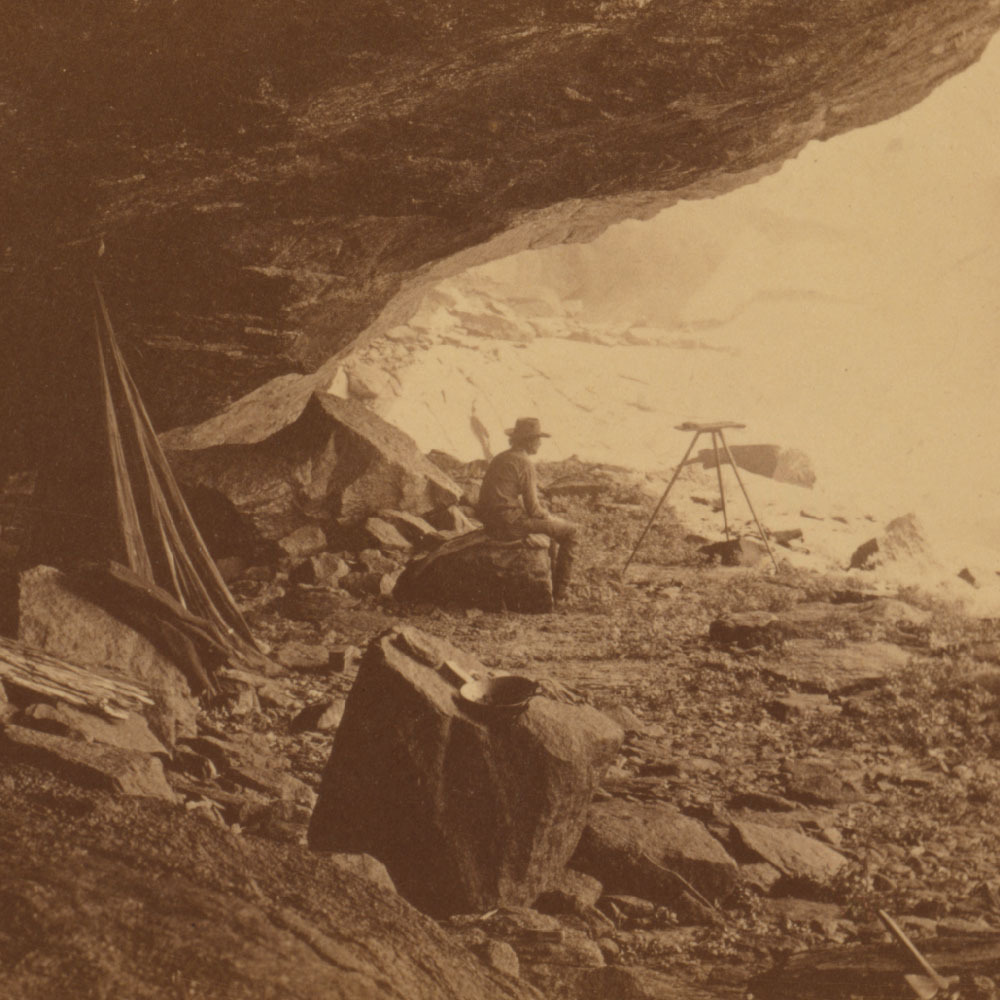

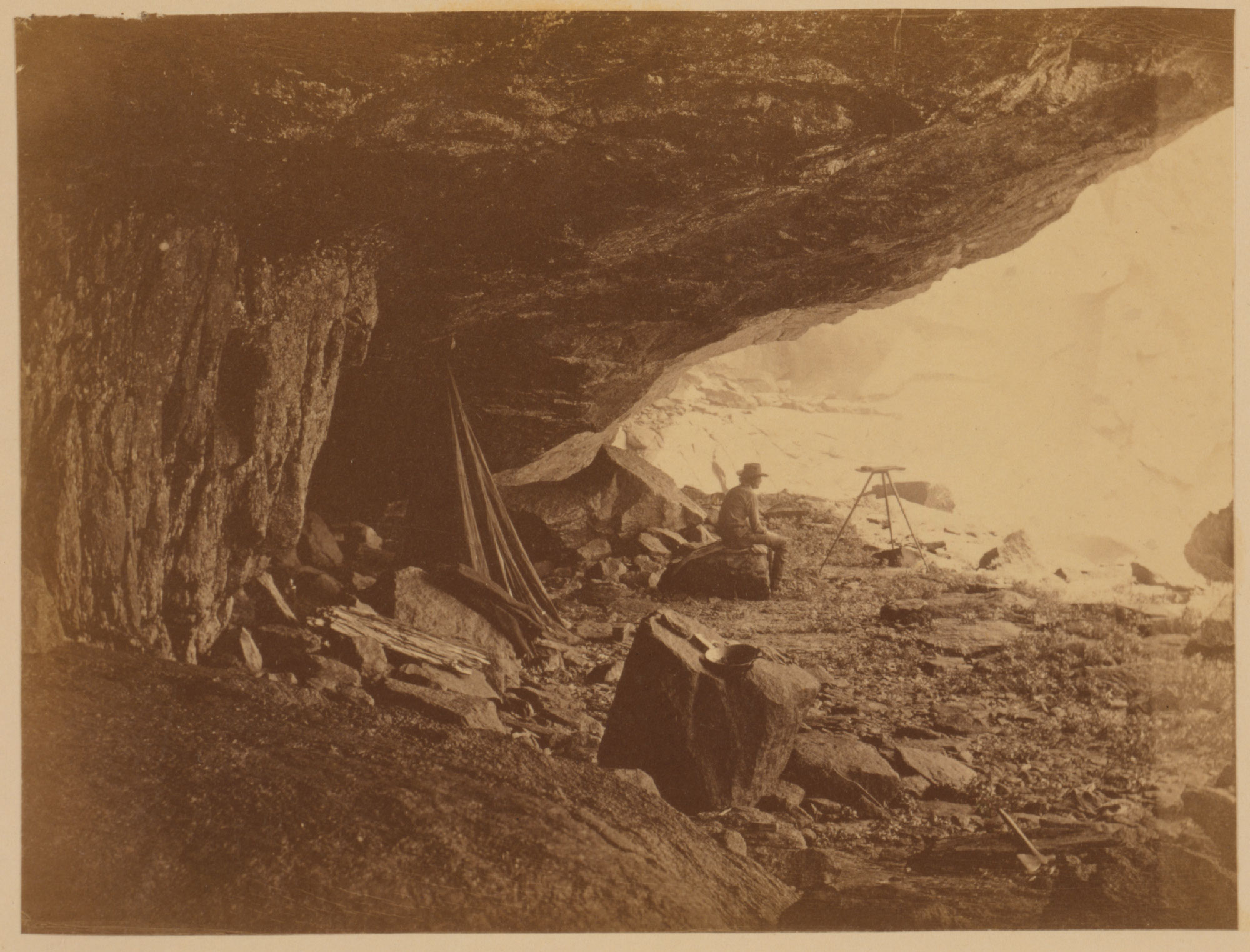

Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, Man Seated Beneath Rock Formation… You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it is a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to the environment.

Next, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understandings of the content.

The prepositional phrase 'for learning' is a succinct, nearly self-explanatory definition of formative assessment; still, it may be helpful for you to revisit the notion. Formative assessment can be understood as a process that centers round activities and assignments intended to promote learners' learning and improve teachers' teaching; students are afforded opportunities to further develop their thinking skills and teachers are provided data with which to adjust subsequent instruction. The explicit focus on improving future learning contrasts sharply with summative assessment (i.e., assessment 'of learning') which primarily features teachers assigning grades for past learning.Which formative assessment opportunities in this lesson are you likely to emphasize? Why?* Callahan, C. (2022). Formative assessment to help students decode, process, and evaluate social studies information. The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies. (83)1After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about conservation and preservation of land. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

For an additional activity you could ask students to connect the lesson’s persistent issue in world history—the balance of national sovereignty and international law—to a government’s practice of using eminent domain to increase conservation easements and accomplish conservation goals. The Follow-on Handout presents students with a photograph of a protest at the Stockholm+50 conference.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback and perhaps a rubric. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: the environment.

You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.In educational circles, the term rubric refers to the important framework of fixed expectations that can be presented to students with an assigned task to communicate learning goals, performance levels, and their associated values. To help promote the skill of self-regulated learning, a rubric could be formatted to function as a type of checklist, affording students the opportunity to compare their performance against expectations prior to formally submitting their work. Decades of research with students from all grade levels and disciplines suggest that rubrics used formatively can help students improve the quality of their work.What one feature of this lesson would you be sure to assess and how would you assess it?* Callahan, C. (2022)Should nations be afforded territorial sea rights and exclusive economic zones around artificial islands?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (economic zones around artificial islands) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try initiating a seemingly impromptu conversation by asking the class: “What do you think of Sealand… is it an independent nation or not?” You could provide more information about this 1-acre island about 6.5 nautical miles east of Suffolk, England in the North Sea. It is a self-proclaimed “sovereign nation.” It has its own constitution, national flag, national seal, and it even has its own passport. It is a constitutional monarchy ruled by Prince Michael. This is an example of a “micronation,” a group that claims to meet all of the criteria for being acknowledged as a sovereign nation, but do not have formal recognition from other nations. While students share their thoughts aloud, you can negotiate responses by categorizing them into broader themes such as what exactly constitutes “a sovereign nation,” and “what logistical concerns (i.e., property ownership, currency) are raised when a region wishes to be independent from another nation?” Together, the class may want to create a list of criteria a sovereign nation must meet. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As the conversation wanes, you can share that today students are going to explore, not the facts about Sealand, but about the global concerns surrounding islands—natural and artificial—and their sovereignty and access to their resources. “Should nations be afforded territorial sea rights and exclusive economic zones around artificial islands?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open-ended questions around which this problem-based historical inquiry (PBHI) activity is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is “territorial seas,” and citizens of many nations throughout the world have had to think through their respective answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should help them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).

PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”

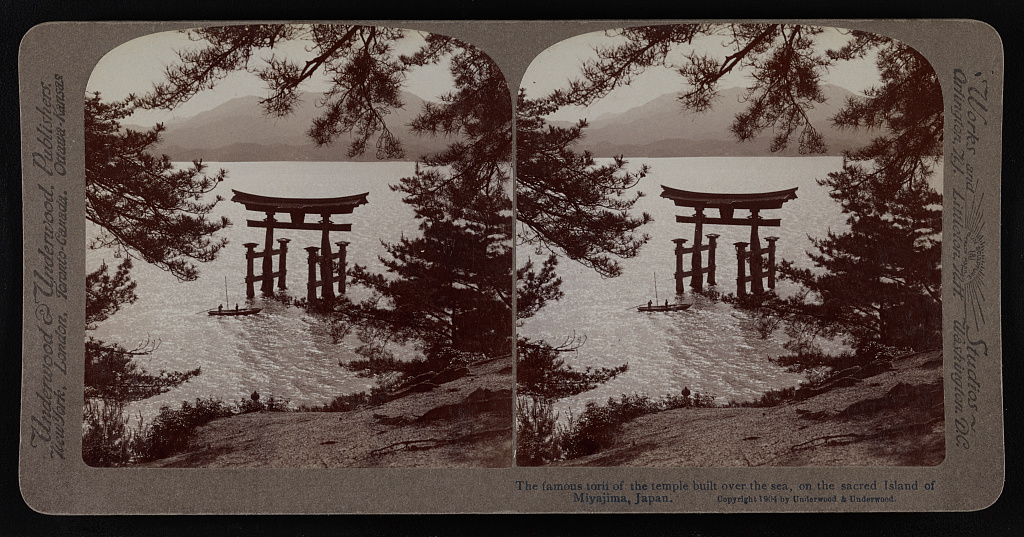

Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, The famous torii of the temple built over the sea, on the sacred Island of Miyajima, Japan. You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it’s a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to territorial seas and exclusive economic zones.The notion of Multiple Intelligences* may be helpful; it attempts to account for the vast array of human abilities. Schools tend to emphasize mostly reading and writing skills, and while many students succeed in that environment, many do not. This notion argues students deserve a broader vision of education where teachers employ different methodologies to design classroom experiences to reach all students. There are seven separate Multiple Intelligences: linguistic, logical mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. Some criticize the notion because of its minimal scientific precision and empirical evidence. Others find Multiple Intelligences helpful for pluralizing instruction and assessment and for addressing differences in students’ needs.What are your thoughts about Multiple Intelligences… and in what ways does this lesson attend to them?* Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. NY:Basic BooksNext, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understandings of the content.

After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about sustainable development, the use of clean energy, and the role of the government to promote those practices. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: territorial seas and

exclusive economic zones.To enhance learning with visual literacy* you could ask students to interpret historical photographs. Visual information inundates our modern lives (i.e., print and online media, computers, cell phones, t.v., billboards, etc.). Students tend to forge their beliefs and values from images, often accepting them as objective and value free recordings of reality. In this lesson, students are to think deeply about photography and its construction—not depiction—of a reality. Students will analyze angles, lighting, fore and back ground content, symbols employed, cropping and more. Critically deconstructing photos can help develop students’ abilities to reflect on messages coming from imagery.What experiences do you have, as a teacher and as a student, with interpreting visual images?* Callahan, C. (2013). Analyzing Historical Photographs to Promote Civic Competence. Social Studies Research and Practice, (8)1You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.

Should nations at war follow generally established “conduct of war” rules?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (the 1864 Geneva Convention, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, and the Russo-Japanese War) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (the 1864 Geneva Convention, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, and the Russo-Japanese War) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try initiating a seemingly impromptu conversation by asking the class: “is it important that a sporting event is played fairly?” While students share their thoughts aloud, you can negotiate responses by categorizing them into broader themes such as what exactly constitutes “sportsmanship” (fair behavior) versus “gamesmanship” (suspect, but not unfair behavior) versus “cheating” (unfair behavior). You may also want to discuss the potential importance of a sporting event being fair, such as respect for competition and self-fulfillment, and in the case for many professional sports, legitimacy for legalized gambling. Students may also talk about potential causes and consequences of sporting events being fair and may want to explore whether a “win at all costs” attitude is just. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As responses wane, you can share that today students are going to extend the conversation to ask, not about sports, but about global conflicts. “Should nations at war follow generally established ‘conduct of war’ rules?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open ended questions around which this problem-based historical inquiry (PBHI) activity is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is “conduct of war,” and citizens of many nations throughout the world have had to think through their respective answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.Problem-based historical inquiry* (PBHI) is an approach to teaching students about the past. One of the tenets of PBHI is that learning should be purposeful: lessons should be centered around open-ended, societal concerns that call for students to engage in real-world problem-solving, make decisions, and act. Lessons should afford students sufficient time for sustained focus on content and skills and to think deeply and seriously about facts, definitions, and values. Instead of memorizing information from a textbook or lecture, students have a more authentic purpose with PBHI: deep, sustained learning and struggling with problems of the past to more meaningfully address problems of their present and future.Which of the two compelling questions presented in this lesson would you center instruction around? Why?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013). Designing web-based educative curriculum materials for the social studies. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2).You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should help them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).

PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to actively collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, A dead war monster—Russian battleship ‘Peresvet’ wrecked by Japanese shells, Port Arthur harbor. You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it’s a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to the conduct of war.

Next, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understanding.PBHI* is also founded on the belief that when properly supported, all students are capable of higher levels of thinking. For students to develop the skills and knowledge needed to be critical thinkers, teachers must appeal to each student’s individual needs, often at the time those needs are presented. It’s called scaffolding when teachers provide the support structures to help learners get to the next level of thinking. Hard scaffolds are the static supports that anticipate general difficulties (i.e., providing definitions for challenging terminology and graphic organizers). Soft scaffolds are dynamic, situation-specific aids to help learners process data, (i.e., just-in-time conversations).Which hard scaffolds and soft scaffolding opportunities in this lesson do you think are the most important?* Callahan, Saye, & Brush. (2013)After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about nations’ rights and duties as they concern the opening of hostilities, the use of sea mines, and neutral nations. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

For an additional activity you could ask students to connect the lesson’s persistent issue throughout world history—the balance of national sovereignty and international law—to the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War. The Follow-on Handout presents students with a photograph of a new laser weapon and asks about the legitimacy of its use.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: conduct of war.

You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.To enhance learning with visual literacy* you could ask students to interpret historical photographs. Visual information inundates our modern lives (i.e., print and online media, computers, cell phones, t.v., billboards, etc.). Students tend to forge their beliefs and values from images, often accepting them as objective and value free recordings of reality. In this lesson, students are to think deeply about photography and its construction—not depiction—of a reality. Students will analyze angles, lighting, fore and back ground content, symbols employed, cropping and more. Critically deconstructing photos can help develop students’ abilities to reflect on messages coming from imagery.What experiences do you have, as a teacher and as a student, with interpreting visual images?* Callahan, C. (2013). Analyzing Historical Photographs to Promote Civic Competence. Social Studies Research and Practice (8)1. 77-88.Who, if anyone, should govern Antarctica?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (land claims in Antarctica) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (land claims in Antarctica) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try asking the question: “Can you name one place on earth that has never had a war, is nearly 100% environmentally protected, and where scientific research is the top priority for its land?” If students need another clue, add “It is larger than Europe and about 98% of it is covered in ice.” Confirm students guesses of “Antarctica,” and explain that today the class is going to explore this land where the first semi-permanent inhabitants arrived in late 18th century. Students may also want to talk about penguins and whales. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As the conversation wanes, you can share that today students are going to explore, not the facts about Antarctica, but about the global concerns surrounding its sovereignty and resources. “Who, if anyone, should govern Antarctica?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open-ended questions around which this inquiry-based lesson is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is “acquiring territory,” and citizens of many nations throughout the world have had to think through their respective answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.Inquiry-based instruction is a powerful teaching approach for international and global education. It can connect concerns or problems shared across the globe to broader historical themes and ask students to develop fair, desirable solutions to those problems.International and global education can be empowering because it centers learning around open-ended questions of worldly significance that encourage students to recognize an interconnectedness between people throughout nations and cultures, explore information from multiple international perspectives, and foster productive cross-cultural collaborative skills.

Which element of this approach—inquiry, interconnectedness, multiple perspectives—may be the most challenging to implement in the classroom? Why? What could help you meet the challenge?

You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should help them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).

PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”

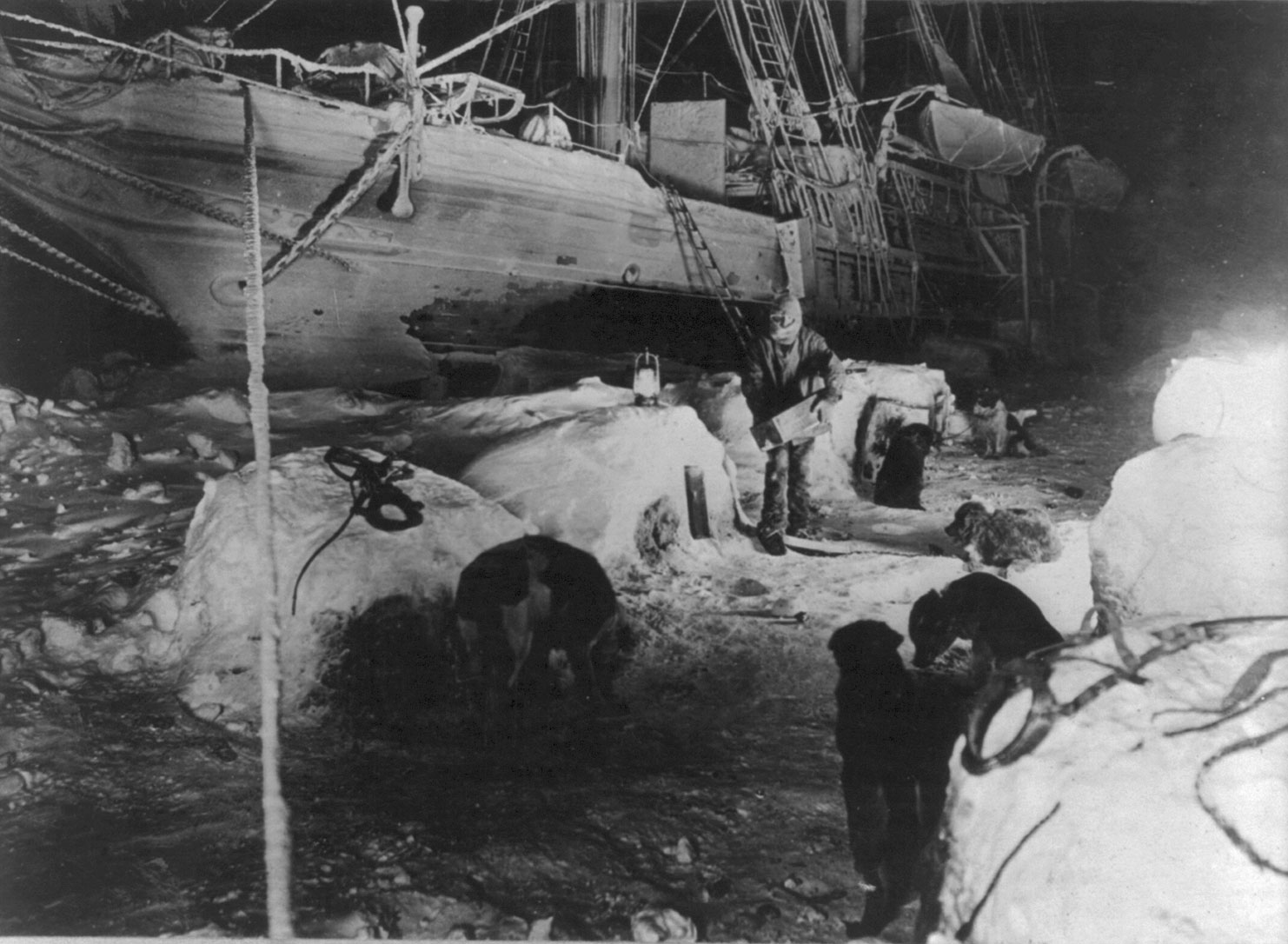

Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, Shackleton’s expedition to the Antarctic faithful dogs being fed in the ice kennel, while Endurance was stuck fast.… You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it’s a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to acquiring territory.

Next, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understandings of the content.After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about sustainable development, the use of clean energy, and the role of the government to promote those practices. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback and perhaps a rubric. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: acquiring territory.In educational circles, the term rubric refers to the important framework of fixed expectations that can be presented to students with an assigned task to communicate learning goals, performance levels, and their associated values. To help promote the skill of self-regulated learning, a rubric could be formatted to function as a type of checklist, affording students the opportunity to compare their performance against expectations prior to formally submitting their work. Decades of research with students from all grade levels and disciplines suggest that rubrics used formatively can help students improve the quality of their work.What one feature of rubrics do you like the most? Is there a feature that gives you pause? Why?

You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.

Should Kosovo be recognized as an independent nation?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (Kosovo’s independence, the First Balkan War, and the Red Cross) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will also develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try initiating a seemingly impromptu conversation by asking the class: “What do you think of Zaqistan… is it an independent nation or not?” You could provide more information about this 2-acre self-proclaimed “sovereign nation” in Box Elder County, Utah. It has its own national flag, national seal, and it even has its own passport. Its president, named Zaq, established Zaqistan in 2005. This is an example of a “micronation,” a group that claims to meet all of the criteria for being acknowledged as a sovereign nation, but do not have formal recognition from other nations. While students share their thoughts aloud, you can negotiate responses by categorizing them into broader themes such as what exactly constitutes “a sovereign nation,” and “what logistical concerns (i.e., property ownership, currency) are raised when a region wishes to be independent from another nation?” Together, the class may want to create a list of criteria a sovereign nation must meet. This class-created list could be compared to the two lists of criteria mentioned later in this lesson. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As responses wane, you can share that today students are going to extend the conversation to ask, not more about Zaqistan or other micronations, but about Kosovo. “Should Kosovo be recognized as an independent sovereign nation?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open-ended questions around which this problem-based historical inquiry (PBHI) activity is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is “national sovereignty,” and citizens of many nations throughout the world have had to think through their respective answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.Problem-based historical inquiry* (PBHI) is an approach to teaching students about the past. One of the tenets of PBHI is that learning should be purposeful lessons should be centered around open-ended, societal concerns that call for students to engage in real-world problem-solving, make decisions, and act. Lessons should afford students sufficient time for sustained focus on content and skills and to think deeply and seriously about facts, definitions, and values. Instead of memorizing information from a textbook or lecture, students have a more authentic purpose with PBHI: deep, sustained learning and struggling with problems of the past to more meaningfully address problems of their present and future.Which of the two compelling questions presented in this lesson would you center instruction around? Why?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013). Designing web-based educative curriculum materials for the social studies. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2).You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own best interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).Another tenet of PBHI* is that learning should be connected. Experts and novices tend to think and solve problems differently due to the ability to demonstrate connections in data. Experts have larger, more interconnected mind-maps. Novices who develop robust mind-maps tend to think deeply because interconnected data is easier to retrieve and it imparts more complex and sophisticated representations of reality. PBHI lessons feature questions that posit authentic concerns for communities. These questions function as mental anchors, to which students can attach both their previous knowledge and newly learned information. Creating robust, interconnected mind-maps may help students understand links between past and present, cause and effect.What are the mental anchors for this lesson?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013)PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”

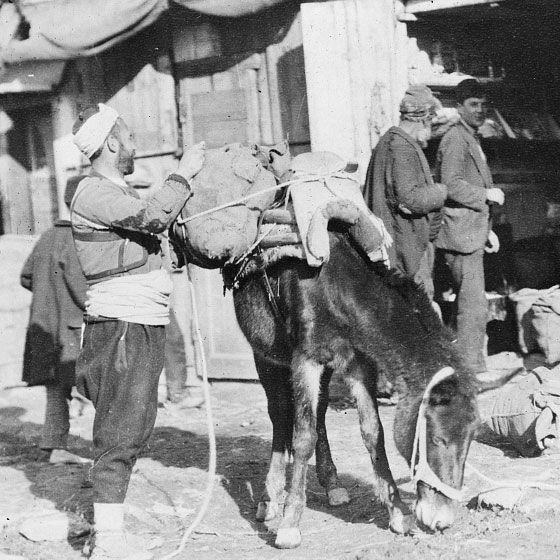

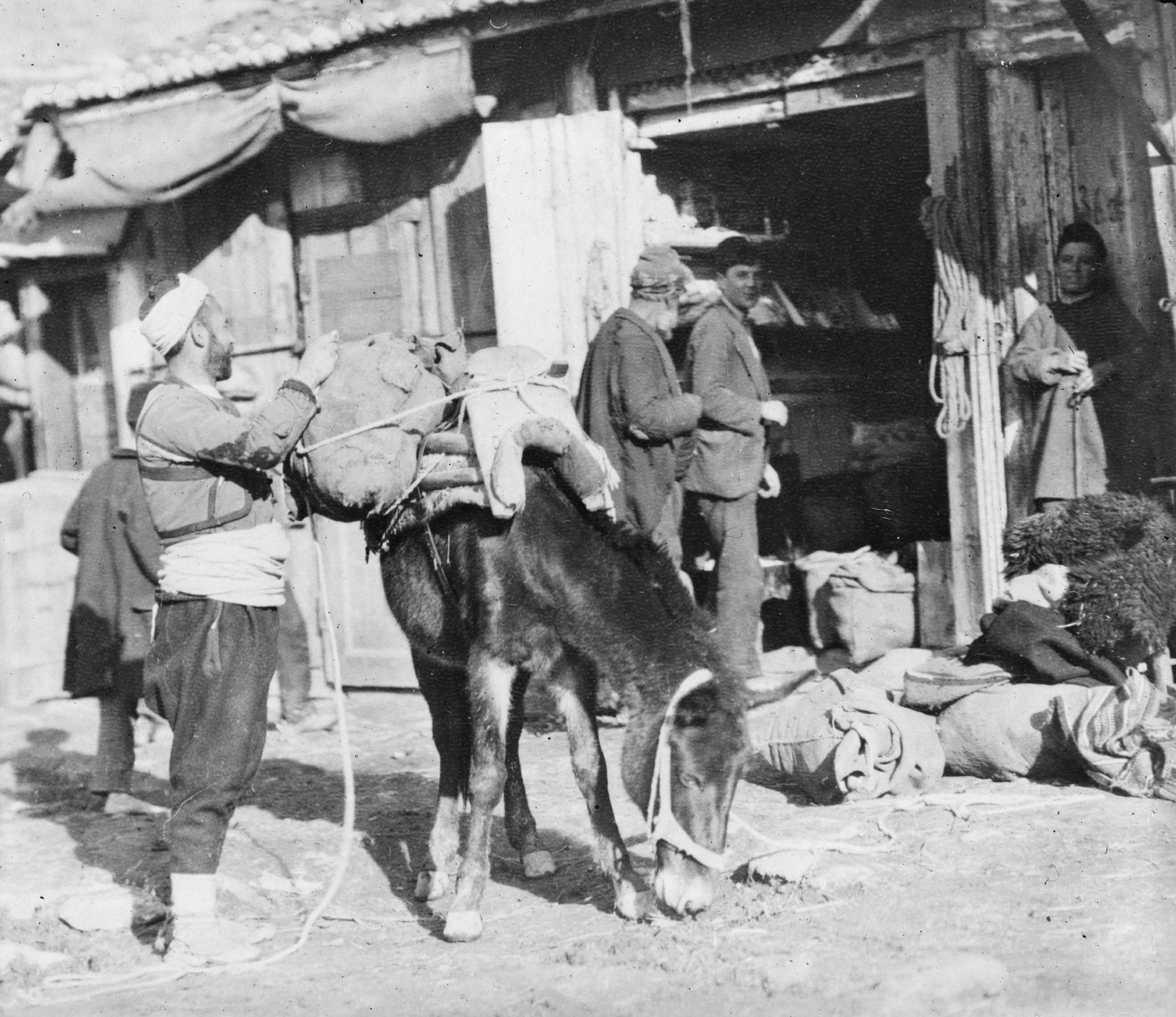

Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, Packing for home… You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it is a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to recognition of sovereignty and independence.The notion of Multiple Intelligences* may be helpful; it attempts to account for the vast array of human abilities. Schools tend to emphasize mostly reading and writing skills, and while many students succeed in that environment, many do not. This notion argues students deserve a broader vision of education where teachers employ different methodologies to design classroom experiences to reach all students. There are seven separate Multiple Intelligences: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. Some criticize the notion because of its minimal scientific precision and empirical evidence. Others find Multiple Intelligences helpful for pluralizing instruction and assessment and for addressing differences in students’ needs.What are your thoughts about Multiple Intelligences… and in what ways does this lesson attend to them?* Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. NY:Basic BooksNext, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understandings of the content.

After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about nations’ recognizing the sovereignty of other (potential) nations. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

For an additional activity you could ask students to connect the lesson’s persistent issue in history—the balance of national sovereignty and international law—to Kosovo’s 2008 Declaration of Independence. The Follow-on Handout presents students with a photograph of a protest in Canada.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: national sovereignty.The prepositional phrase 'for learning' is a succinct, nearly self-explanatory definition of formative assessment; still, it may be helpful for you to revisit the notion. Formative assessment can be understood as a process that centers round activities and assignments intended to promote learners' learning and improve teachers' teaching; students are afforded opportunities to further develop their thinking skills and teachers are provided data with which to adjust subsequent instruction. The explicit focus on improving future learning contrasts sharply with summative assessment (i.e., assessment 'of learning') which primarily features teachers assigning grades for past learning.Which formative assessment opportunities in this lesson are you likely to emphasize? Why?* Callahan, C. (2022). Formative assessment to help students decode, process, and evaluate social studies information. The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies. (83)1You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.

When should nations agree to ‘pause’ their production of weapons?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (the 1921 Washington Conference; disarmament efforts after the Great War) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try initiating a seemingly impromptu conversation by asking students: “should there be a ‘pause’ on the development of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) systems?” While students share their thoughts aloud you can share arguments from both sides including from researchers who wrote an open letter that advocated for a pause to afford technology companies and government regulators time to craft protections from the risks of artificial intelligence. You may also want to discuss the potential harms (AI systems can be disinformation engines, perpetuate systemic bias, and exactly reproduce personally identifiable information1) and benefits (automation, productivity, data collection and complex problems-solving2). Students may also talk about potential causes and consequences of AI systems being totally banned or totally limitless. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As responses wane, you can share that today students are going to extend the conversation to ask, not about AI, but about global conflicts. “When should nations agree to ‘pause’ their production of weapons?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open-ended questions around which this problem-based historical inquiry (PBHI) activity is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is disarmament,” and citizens of many nations throughout the world have had to think through their respective answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.Problem-based historical inquiry* (PBHI) is an approach to teaching students about the past. One of the tenets of PBHI is that learning should be purposeful lessons should be centered around open-ended, societal concerns that call for students to engage in real-world problem-solving, make decisions, and act. Lessons should afford students sufficient time for sustained focus on content and skills and to think deeply and seriously about facts, definitions, and values. Instead of memorizing information from a textbook or lecture, students have a more authentic purpose with PBHI: deep, sustained learning and struggling with problems of the past to more meaningfully address problems of their present and future.Which of the two compelling questions presented in this lesson would you center instruction around? Why?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013). Designing web-based educative curriculum materials for the social studies. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2).You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should help them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).

PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to actively collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”Another tenet of PBHI* is that learning should be active: students should collaborate to interpret rich, diverse historical documents as a means to develop an understanding of the past and the different sides of a historical event. This collaboration should feature students using disciplinary skills (i.e., thinking “historically” or “geographically,” etc) and evidence to support an answer to the open-ended question around which the lesson is centered. No individual alone can perceive the complexity of social reality, thus a student attempting to understand the past needs the help of others—students and teachers—who, through discourse and deliberation, can reason together meaningfully about events.What aspect of student collaboration seems the most challenging to you, the classroom teacher?* Callahan, Saye, & Brush. (2013).Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, Just men, but mighty important ones! The “Big Nine” at the World Disarmament Conference, Washington, D.C., 1921. You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it’s a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to disarmament.

Next, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding.

Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understanding. After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about nations’ rights and duties as they concern disarmament. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.PBHI* is also founded on the belief that when properly supported, all students are capable of higher levels of thinking. For students to develop the skills and knowledge needed to be critical thinkers, teachers must appeal to each student’s individual needs, often at the time those needs are presented. It’s called scaffolding when teachers provide the support structures to help learners

get to the next level of thinking. Hard scaffolds are the static supports that anticipate general difficulties (i.e., providing definitions for challenging terminology and graphic organizers). Soft scaffolds are dynamic, situation specific aids to help learners process data, (i.e., just-intime conversations).Which hard scaffolds and soft scaffolding opportunities in this lesson do you think are the most important?* Callahan, Saye, & Brush. (2013)PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: disarmament.

You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.

1 see Clarke, L., (April 11, 2023) Alarmed tech leaders call for AI research pause. Science.

2 see Maheshwari, R. (April 11, 2023). Advantages Of Artificial Intelligence (AI) In 2023. Forbes Advisor.Should humans establish settlements on Mars?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (the Cold War and new technological advances in spacefaring) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will also develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (the Cold War and new technological advances in spacefaring) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will also develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question. PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try initiating a seemingly impromptu conversation by asking the class: “What does everyone think of human spaceflight… if the half-a-million-dollar flight were offered to you free of charge, would you go on a commercial flight into space?” You could provide more information about types of commercial spaceflights (i.e., lunar orbit, visits to the international space station, etc.). Students may not be particularly interested in spaceflight; however, the very fact that human spaceflight exists is the important concern for this conversation. While students share their thoughts aloud, you can negotiate responses by categorizing them into broader themes such public and private spaceflights, the personal and community benefits and costs, and—importantly—what the future of such spaceflights may hold. Together, the class may want to create a list of benefits of spaceflight and space exploration in general and contrast those with its financial costs. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

As responses wane, you can share that today students are going to extend the conversation to ask, not more about the spaceflights, but about the national and international consequences of space exploration. “Should humans establish settlements on Mars?” could be the question for today; however, you could also choose to focus on the larger question: “What’s the proper balance between national sovereignty and international law?” These are the open-ended questions around which this problem-based historical inquiry (PBHI) activity is centered. The questions work well with the previous conversation and the subsequent learning segments because one of the domains of international law is outer space and citizens of many nations have had to think through their answers. This is truly a persistent issue in world history.Problem-based historical inquiry* (PBHI) is an approach to teaching students about the past. One of the tenets of PBHI is that learning should be purposeful lessons should be centered around open-ended, societal concerns that call for students to engage in real-world problem-solving, make decisions, and act. Lessons should afford students sufficient time for sustained focus on content and skills and to think deeply and seriously about facts, definitions, and values. Instead of memorizing information from a textbook or lecture, students have a more authentic purpose with PBHI: deep, sustained learning and struggling with problems of the past to more meaningfully address problems of their present and future.Which of the two compelling questions presented in this lesson would you center instruction around? Why?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013). Designing web-based educative curriculum materials for the social studies. <i>Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education</i, 13(2).You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should them begin to explore the balance between a

what a nation wants to do in its own best interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and connect it to their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).Another tenet of PBHI* is that learning should be connected. Experts and novices tend to think and solve problems differently due to the ability to demonstrate connections in data. Experts have larger, more interconnected mind-maps. Novices who develop robust mind-maps tend to think deeply because interconnected data is easier to retrieve and it imparts more complex and sophisticated representations of reality. PBHI lessons feature questions that posit authentic concerns for communities. These questions function as mentalanchors, to which students can attach both their previous knowledge and newly learned information. Creating robust, interconnected mind-maps may help students understand links between past and present, cause and effect.What are the mental anchors for this lesson?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013)PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”

Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, The U.S. Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama. You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it is a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to outer space.Another tenet of PBHI* is that learning should be active: students should collaborate to interpret rich, diverse historical documents as a means to develop an understanding of the past and the different sides of a historical event. This collaboration should feature students using disciplinary skills (i.e., thinking “historically” or “geographically,” etc) and evidence to support an answer to the open-ended question around which the lesson is centered. No individual alone can perceive the complexity of social reality, thus a student attempting to understand the past needs the help of others—students and teachers—who, through discourse and deliberation, can reason together meaningfully about events.What aspect of student collaboration seems the most challenging to you, the classroom teacher?* Callahan, C., Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2013)Next, place students into small groups of four or five, it would be best to make these groups prior to the day of the lesson and attend to students’ strengths and potential limitations, personalities, and multiple intelligences. Then, proceed with the analysis of the photograph. Give the groups approximately 10 minutes to actively think together about the photograph “historically” following the components listed on the Student Handout. It’s very important during this time that you to move about the room, visit with each group, initiate conversations regarding their historical thinking, and offer specific, individualized feedback: this is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is often very helpful for guiding students toward deeper understandings of the content.

After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about commercial spacefaring and the recovery and use of space materials. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to another group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

For an additional activity you could ask students to connect the lesson’s persistent issue in history—the balance of national sovereignty and international law—to SpaceX’s Mars Program that plans the eventual colonization of Mars. The Follow-on Handout presents students with a photograph of the surface of Mars.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback and perhaps a rubric. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: outer space.To enhance learning with visual literacy* you could ask students to interpret historical photographs. Visual information inundates our modern lives (i.e., print and online media, computers, cell phones, t.v., billboards, etc.). Students tend to forge their beliefs and values from images, often accepting them as objective and value free recordings of reality. In this lesson, students are to think deeply about photography and its construction—not depiction—of a reality. Students will analyze angles, lighting, fore and back ground content, symbols employed, cropping and more. Critically deconstructing photos can help develop students’ abilities to reflect on messages coming from imagery.What experiences do you have, as a teacher and as a student, with interpreting visual images?* Callahan, C. (2013). Analyzing Historical Photographs to Promote Civic Competence. Social Studies Research and Practice, (8)1You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.

Should the US reward consumer behaviors that help achieve sustainable development goals?

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (climate change and the environmental movement) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will also develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.