This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (land claims in Antarctica) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

This 45-minute lesson is designed to help students explore historical events (land claims in Antarctica) in context of a persistent issue throughout history: national sovereignty v. international law. Students will develop skills and habits of mind associated with thinking critically about visual information. The lesson features a three-part teaching strategy. First, you’ll lead an informal class-wide conversation that culminates in an open-ended question; Second, you’ll support students as they interpret a historical photograph; Third, you’ll encourage students to begin to answer the question.

PART 1: THE CONVERSATION (10 minutes): Try asking the question: “Can you name one place on earth that has never had a war, is nearly 100% environmentally protected, and where scientific research is the top priority for its land?” If students need another clue, add “It is larger than Europe and about 98% of it is covered in ice.” Confirm students guesses of “Antarctica,” and explain that today the class is going to explore this land where the first semi-permanent inhabitants arrived in late 18th century. Students may also want to talk about penguins and whales. Remember: this is not intended to be a lengthy, formal discussion. Rather, it’s a brief grabber to gather students’ interest. Be mindful of your time and stay focused.

You might also share that today, instead of bookwork, worksheets, or a lecture, students will gather information and take notes from critically analyzing a historical photograph. Thinking deeply about this photograph should help them begin to explore the balance between a what a nation wants to do in its own interest (national sovereignty) and what other nations want it to do (international law or concern). You may want to click HERE to read a helpful one-page “Fact Sheet” from the United Nations that discusses International Law.

As a transition from the conversation and whichever open-ended question you decide to emphasize, you should share with students that the skills they will sharpen today are essential for 21st century citizenship. You can remind students that there are, and will likely always be, people and groups who intentionally use images to influence their decision-making (i.e., how to spend money, who to vote for). You can share that today students will think about a historical photograph, using it as evidence to build a claim about an open-ended question, but they hopefully will be able to take that authentic skill and use it to improve their lives away from school (i.e., as they encounter visual information such as advertisements and social media).

PART 2: THE HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPH (25 minutes): Next, make available to each student a copy of the Student Handout. This is a type of data retrieval chart designed for this lesson and students are strongly encouraged to collect their thoughts on it. Explain that thinking critically about images is very different from casually glancing at them. You might want to draw students’ attention to the handout that, by careful design, concentrates their analysis toward thinking deeply and “historically.”

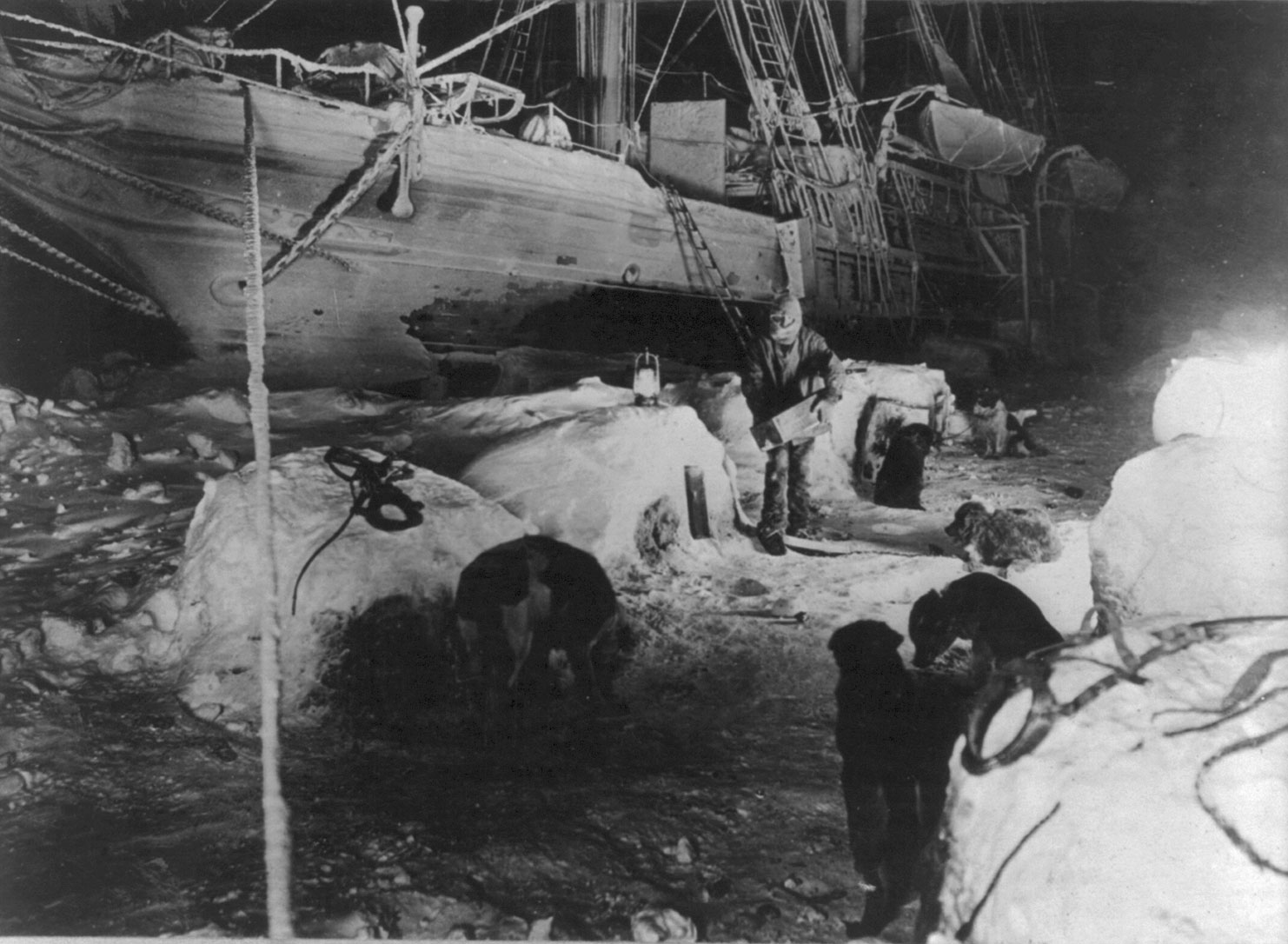

Once each student has a copy of the data retrieval chart, you should make available the photograph, Shackleton’s expedition to the Antarctic faithful dogs being fed in the ice kennel, while Endurance was stuck fast.… You could project the photograph as a multimedia presentation slide and have students work together as a whole class. Or you could ask each student to access a digital copy of the photograph and have them work individually. This lesson plan encourages you to have students work in small groups of about four or five; however, it’s your decision how to implement the lesson.

Regardless of how you make the photograph available to students, you’ll need the Teacher Handout designed specifically for this lesson. It would be best to study the handout well before leading students through this lesson because it’s a primer for the photograph that provides information and a script of talking points for skillfully guiding students in an exploration of how nations tend to deliberate national sovereignty and international law as it relates to acquiring territory.

After the groups have analyzed the photograph and completed the Student Handout, gather the attention of the whole class and have students from each group share their respective group’s observations, conclusions, and thoughts. Be sure to ask their thoughts about sustainable development, the use of clean energy, and the role of the government to promote those practices. Follow these questions by asking for the rationale underpinning their answers. Go out of your way to ask two or three groups to respond to other group’s findings, thus developing a conversation among the students to help everyone discover and create a meaningful understanding of international law. Carefully negotiate students’ responses and keep this segment of the lesson focused.

PART 3: THE ANSWER (10 minutes): After students have analyzed and discussed the historical photograph, ask them to formally to use the skills built and information gathered from today to address the open-ended question you posited earlier. You could ask students to create and submit a 1-minute video or send you an email with their answer. Or they could write their answer on the back of the data retrieval chart; regardless of what tools students use to answer the question, it’s important that you provide each student with individualized, formative feedback and perhaps a rubric. To produce a truly comprehensive answer to such a complex issue, students will need more than just today’s lesson. Still, they should be able to to craft a preliminary answer to the question in regard to one of the domains of international law: acquiring territory.

You can end this lesson by reiterating how the skills and habits of mind practiced today have tremendous value in everyday life, especially considering the amount of visual information produced and consumed on social media platforms.